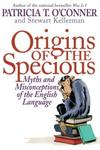

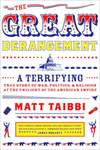

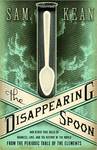

The Rise and Fall of the Galactic Empire by Chris Kempshall

The best fictional worlds invite you to lose yourself in them. They get into your head, makes you wonder what else is there, between the words on the page and beyond the beginning and the end.

Star Wars, of course, is exactly that kind of fiction. What started with a fairly simple space adventure nearly fifty years ago has blossomed into an expansive, living universe, where every new story carries within it the seeds for another story and another one after that. Through the media of film and television, animation and comic books, novels and short stories, Star Wars has built up a world and a history that you could spend your entire life exploring.

Kempshall reflects in the afterward that, for the time he was working on it, it became his whole life. And I certainly can’t blame him for it.

The Rise and Fall of the Galactic Empire is a thorough, insightful history of the Empire from inside the Star Wars universe. Written by historian Beaumont Kin soon after the fall of the New Republic, the Battle of Exegol, and the (probably) final death of Emperor Palpatine, this book attempts to understand how the Empire arose, what its means and methods were, and why, even after the Battle of Endor, its ideology persisted and became the First Order.

It begins with an examination of Sheeve Palpatine and how he rose to power. With the advantage of time, and the testimony of people like Luke Skywalker and Leia Organa, Kin is able to see the Senator from Naboo for who he really was – a master of the Dark Side of the Force, apprentice to a terrible Sith lord, who had decided from his early years that he wanted only one thing: complete mastery of the Galaxy. It follows his career through the Clone Wars, a conflict in which Palpatine, acting as both the Supreme Chancellor and the malicious Darth Sidious, was controlling both sides.

With his power assured, the history then goes on to explore how the Empire functioned, how it expanded, and how it devoured everything in its way. An Empire which rewarded cruelty, blind loyalty, and rampant consumption was everything that Palpatine wanted, and its apotheosis was the Death Star.

Nevertheless, there was resistance, and the history explores that as well. How even with an Empire so comfortable with conflict and aggression might still miss the signs of organized rebellion and even encourage it with its unrepentant use of force and terror.

From there, the book chronicles the assumptions and errors that the Empire made in dealing with the Rebellion, how the loss of figures like Grand Moff Tarkin crippled the Empire’s efforts, and how even though battles like those at Hoth looked like Imperial victories, they did more damage to the Empire than to the Rebellion.

This book is a well-written, detailed, and satisfying look at the history of the stories that we know so well. It draws from not only the films, but also comics, books, and television – any source available that explains the events surrounding the rise of the Empire, the Galactic Civil War, and the Empire’s fall and rebirth.

What makes this book believable is not only that it was written with the full help of the lorekeepers and writers of the Star Wars universe, but that it was written by an actual historian. Kempshall has been writing on war, especially World War One, and found himself in the very enviable position of being able to write a history of one of the most popular fictional universes of our time.

One aspect of this book that is truly fascinating is to see the places where the narrator, Beaumont Kin, lacks information that we, fans of the stories, absolutely have. For example, we all saw the fateful meeting at the beginning of A New Hope where Vader nearly force-chokes Admiral Motti to death. Kin, however, relies only on Motti’s own paperwork, referring to “an almost entirely redacted incident report within the Imperial Archives submitted by Admiral Motti immediately after that summit took place, presumably about something that happened to him during it.”

There are plenty of other places and references that Kempshall includes where he knows that fans of Star Wars will be able o fill in the gaps, having read the books and watched the cartoons, movies, and TV shows. Even more interesting is what he leaves out. There is no mention, for example, of Obi-Wan Kenobi and his role in the rescue of Vader’s children, or Yoda’s training of Luke. Ahsoka Tano, despite her role as the mysterious Fulcrum, is barely mentioned. Dr. Aphra, despite her strange and constant relationship with Darth Vader, only shows up a couple of times, usually in footnotes.

If there is one point of irritation that I have with this book, it’s the way that citations are handled.

It is great that this book is heavily cited – a proper history book should reveal its sources, allowing a reader to go and investigate for themselves, should they want to. The problem is, all of these are in-universe citations. So you might be directed to “New Republic Archives, Section: Adelphi Base, File: Requisition Form #1837p—Subcontract for fulfillment of refuse collection” if you want to know more about how New Republic officers used bounty hunters to go after Imperial remnants.

Now I appreciate kayfabe as much as the next guy, but a lot of these footnotes seemed like they should be pointing at specific literary sources – a show or a comic or something like that – and I really wanted to know what those were. I was hoping that, at the end of the book, there might be a listing of all the sources that Kempshall went to, but alas, there is none. This is a great, but missed opportunity.

The most striking thing, though, was not so much how well it recontextualized the Star Wars universe (and brought more sense to the Sequel Trilogy), but how relevant it was to our world. The rise of fascism, cruelty disguised as order, the seduction of ideology are all familiar to us. The book’s exploration of power and its misuse is painfully on-point, from the terrors of Fascist Europe all the way to the present day. It holds up the grand, sweeping tale of Star Wars as not only an allegory for past conflicts, but as a mirror to our own lives, our own willingness, perhaps, to allow wickedness to be done in our names.

Where the fictional historian narrator becomes angry or sad or frustrated with the terrible works that the Empire performed, you can easily understand how perhaps Kempshall is feeling the same way about our world.

We may not have a Sith Lord running things out here, but we do have petty, power-hungry tyrants; we have people willing to do terrible things because they were told to do them; we have leaders willing to ignore tragedy after tragedy because doing something about it is inconvenient.

This book would be an excellent addition to the collection of any Star Wars fan, and is the perfect answer to those people online who wish, against all available evidence, that Star Wars hadn’t suddenly gotten “all political.” It hasn’t gotten political – it always has been.

“The role of a historian—my role as a historian—is to try to tell you not just how but why these things happened. To try to make you understand the importance of these past events and what they mean for us today and tomorrow.”

Chris Kempshall at Penguin Random House

The Rise and Fall of the Galactic Empire on Goodreads