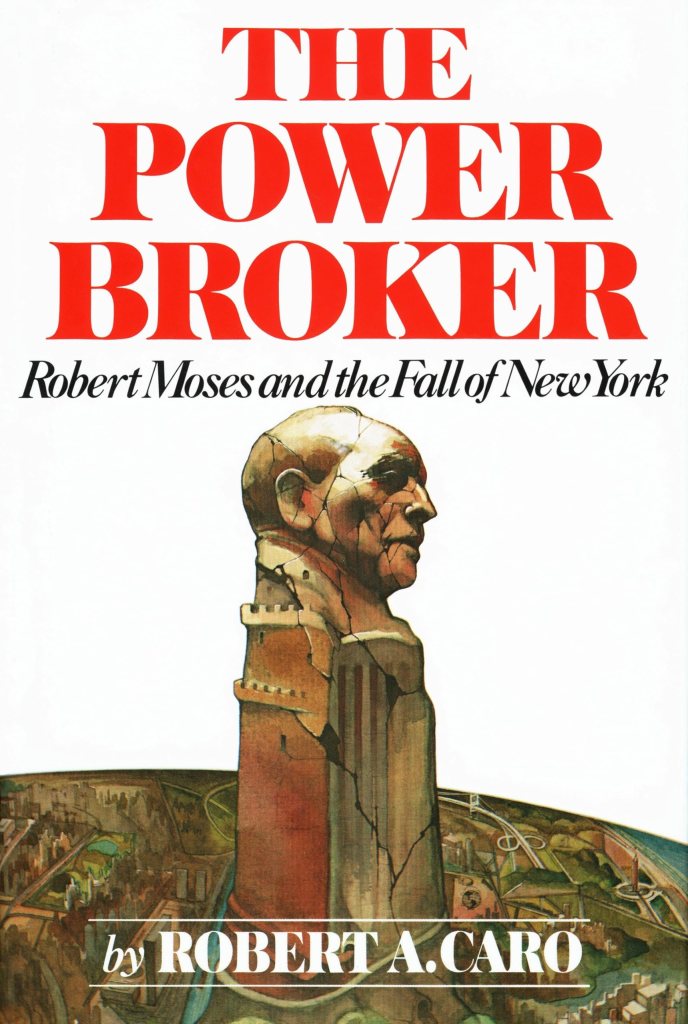

The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York by Robert Caro

Yes, it’s been a little while. Thank you for your patience.

I decided to read The Power Broker mainly because of the series “The Unsleeping City” over on Dropout, an actual play D&D game that’s set in a version of New York City that is steeped in magic and the supernatural, hidden from its normal inhabitants by an Umbral Arcana. In this game, the Big Bad Guy was a man named Robert Moses, a lich who tries to carve out New York as a magical realm all his own. On top of that, he tries to re-define the American Dream into something which fits his particular vision of what the ideal American should be: rich, male, and white.

Imagine my surprise when I found out the not only was Moses a real guy, but that he was just as bad – if not worse – than Brennan Lee Mulligan’s lich.

That’s an oversimplification, of course. If you want it in detail, read all 1300 pages or so of Caro’s book, and you’ll see that while yes, there were improvements done to New York City that were undoubtedly good in the long run, there were just as many that were harmful. And not just harmful in the moment, like tearing down neighborhoods to make room for expressways, but harmful for generations. Moses himself very likely believed that he was doing what was best for New York City. Unfortunately, he never allowed anyone to ever even suggest that he might be wrong.

Caro’s book starts with an understanding of where Moses came from – an affluent Northeast family with a fondness for civic matters and a certain patrician attitude towards helping poor Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe learn how to be good Americans. Moses went to Yale and Oxford, and came back with a desire to get into civil service, with a focus on city improvement. What’s more, he wanted to break the hold that moneyed and special interest groups, such as the infamous Tammany Hall, had on city government by placing people not according to their connections, but according to how well-suited they were for the job.

Ironically, it was through strong personal connections that he had through people such as Governor Al Smith that Moses got a job that he had no experience in: managing parks. To be fair, I don’t think anyone had experience with this in the 1920s and 30s, so I can’t really fault him for that.

Moses turned out to be a man possessed of an amazing mind.

He was imaginative – he could look at a stretch of undeveloped land or a bend in a river or a set of hills and know immediately not only what he wanted to do with it, but how it could be done. To hear tell of it, it was like the vision of a finished improvement or project would simply spring to his mind, and he would be ready to go.

He was intelligent – he had an excellent memory for people and legislation, and was considered one of the best bill drafters in New York. He knew how to craft legislation in such a way that seemingly unrelated, yet wholly interlocked, pieces came together to allow him to get the result that he wanted.

He knew people – he was able to create almost cultlike loyalty in his “Moses Men,” the army of engineers, aides, secretaries and other professionals who worked for him over the years. These people were at his beck and call, obeying every order he gave, affirming every vision he had, and acting as his eyes, ears, and hands throughout the government and civil society of New York.

He was relentless – what Robert Moses wanted, he got. Full stop. Whether he used flattery and kickbacks and “gifts” to get it, or whether he utterly destroyed someone’s reputation in the press or in their industry, there were no lengths that Moses would not go to in order to accomplish his goals. He was almost incapable of taking “no” for an answer when it came to his projects.

And therein, I think, lies Moses’ real tragedy, and the reason why (to me) Caro’s book comes across as spectacularly angry.

With the skills and resources available to Robert Moses, he could have built a New York City that would have been a model for a humane, livable city for the ages. He could have built a place that would inspire better communities, better living, a model of how to make a city a place of growth and humanity.

He did not want that, though. Robert Moses loved parks and cars, and that was pretty much it. His answer to most problems of the city was either to build a park (whether or not one was needed) or to build a road. In his time with the city, he built more than a dozen major bridges and hundreds of miles of highways. He built out the highways that turned Long Island into a major New York suburb. He built the expressways that bracket Manhattan, and would have built more if he had been able to.

Unfortunately, a growing city does not need more roads. In fact, as Caro’s book points out, more roads actually make traffic problems worse. It is public transportation – busses and subways – which make a city really work, allowing so many people to live and work in such a densely packed place. But Moses hated public transportation.

Public transportation, you see, would allow poor people to get to his pretty parks. And he wanted none of that.

A very famous anecdote from the book is that, in designing the roads to his beloved Jones Beach, Moses had the overpasses designed at a height that would be too low for busses to access. So, if you had a car (i.e. money), then welcome to the beach! If you were a poor person, though, you’re out of luck. No busses for you. And Moses much later said that he knew he didn’t need to try and get legislation passed to ban busses and The Poor. Laws and regulations, after all, could be changed.

It’s really tough to rebuild a bridge. Or, more to the point, several hundred bridges.

Later, when he got himself involved in other areas of civic improvement, he tore down perfectly good neighborhoods in order to make room for his roads and public housing. These neighborhoods, like Tremont or Third Avenue might not have been wealthy neighborhoods, but they were good ones. Places where people knew each other, had businesses, raised families. Some of them were perfect places for new residents to prepare for living in a city such as New York – they could learn basic city living in Tremont, for example, and then, when ready, move elsewhere.

But Moses wanted that land. He wanted it to build his precious roads and bridges. He wanted it to build public housing that would enrich his political allies. He wanted it so that he could exert power over the city and over the people who made the city work. He, like the Robert Moses of “The Unsleeping City,” wanted to reshape New York in his image, to make it the place he felt it should be rather than the place its citizens needed.

All throughout this book, I could feel Caro walking a thin line. As a biographer, he clearly wanted to be as fair as he could to Moses, but with each passing chapter, I could see that being harder and harder to accomplish. In the chapter “One Mile,” which describes the destruction of Tremont for the Cross-Bronx Expressway, you can imagine Caro begging us, or someone, to tell him what the point of all this was. Why good people had to lose their homes and their lives just so a few other people could get stuck in a traffic jam in the Bronx.

The answer, of course, is because that’s what Robert Moses wanted. And what Moses wanted, he got.

Ultimately, as the title suggests, this is a book about power. About how power is wielded and how it reveals the true nature of people. Young Moses believed himself to be an anti-corruption reformer, the champion of good government and the people. But power revealed that he was anything but.

It’s a chillingly relevant book to read here in the Age of Trump, where we have another ambitious man who is very good at attaining and wielding power in order to fulfill his own selfish dreams of what the nation should be. I don’t think Moses and Trump are really comparable, though. Moses’ dreams for New York were ambitious and grand, and he had an encyclopedic knowledge of politics, infrastructure, and geography.

Trump barely pays attention to the world or facts or anything like that, and doesn’t have any interest in actually learning anything. But, just like Moses, he has power. And he knows very well how to gain and hold on to power.

So what do we do about it? Caro’s book won’t really make you feel any better about this – the only real reason Moses fell from grace is that he went up against someone who wasn’t awed or intimidated by him, and that was Governor Nelson Rockefeller. When Moses used one of his classic techniques to get what he wanted – threaten to resign and thereby throw all his public authorities and projects into disarray, where previous governors had caved, Rockefeller said, “Okay. Have your resignation on my desk in the morning.” That was the first real, substantial crack in Moses’ power and his ability to wield it in New York, and within a decade, he was out.

Maybe that’s the way to deal with people like him and Trump. Call their bluffs. Make them put up or shut up. Expose them for who they are, rather than who they pretend to be. Be willing to tell them that they’re wrong, and stand up for that.

If there’s any real, practical lesson to be taken from this book, I think that’s it. There will always be people who are good at moving the levers of power, and it’s up to the rest of us to watch them very closely. And, if necessary, have the courage to take them down.

“An idea was no good without power behind it, power to make people adopt it, power to reward them when they did, power to crush them when they didn’t.”

Robert Caro on Wikipedia

The Power Broker on Wikipedia

Robert Caro’s website

The Power Broker Book Club